A PORT TOO FAR

THE BRITISH IN BREST 1944

On this 80th anniversary of the remarkable story of the D Day landings it is all too easy to forget that everything did not go to plan. Eisenhower himself warned that “No plan survives first contact with the enemy”.

The Port of Brest, the largest naval base in Northern France was one of the key initial objectives for Operation Overlord. The extraordinary innovations of Mulberry harbours and the PLOTO would enable the allies to gain a foothold, but soon enough the thousands of men and more importantly their equipment would need a secure modern port able to handle the millions of tons of fuel, ammunition and food required to keep the Allied army supplied. Brest was an obvious choice, a major American base 24 years earlier, well known to the US senior commanders, several of whom had disembarked there as young officers on their way to the Western Front in World War One.

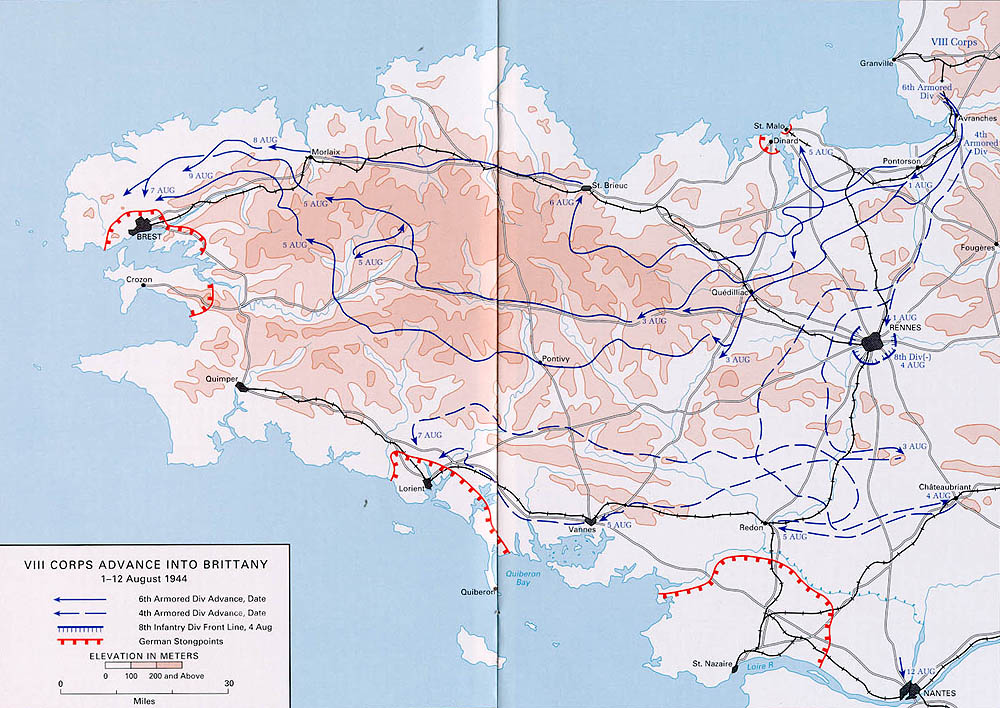

The D Day planners could not predict that the breakout from Normandy would head North or that the German retreat to Paris would be so rapid. When the gruelling battle through the Normandy Bocage finally achieved a breakthrough on 31 July, The US 6th Armoured Division were ordered to head West into Brittany.

Part of the division split off to attempt to capture the smaller but nearby port of St Malo (garrison surrendered 17 August)

The first US army units reached the villages outside Brest on 7 August. But the German garrison proved larger than anticipated. The time taken to reinforce the US allowed the Germans to double the garrison to over 40,000 military personnel around a core of the elite 2nd. Fallschirmjäger (paratroop) Division.

On 26 August the Americans, with the 6th Armored Division replaced by US Army 2nd, 8th and 29th Divisions plus the 2nd and 5th Ranger battalions began their assault on the city. The following weeks saw a gruelling and bitter battle as the Americans sought to overcome the garrison’s well-prepared defences based around the original 18th century Vauban style fortifications.

Although predominantly an American operation the local French resistance played a crucial role in holding territory until the US army reinforcements were available. Specialised British Units were also engaged, notably the battleship HMS Warspite, the Crocodile tanks of 141st Royal Armoured Corps (the Buffs) and the 30th Assault Unit Commandos, whose secret mission is little known.

When the Brest Garrison finally surrendered over a month later, on 18 September, the US Forces had lost 9,831 casualties, the Germans around 12,000 with 38,000 taken prisoner. The bodies of the British and American soldiers who lost their lives were later reburied in CWGC and ABMC cemeteries in Normandy.

But by then the main Allied advance to the north had already reached the port of Antwerp. On 17 September Gen Montgomery launched Operation Market Garden to capture the bridges over the Rhine. If Arnhem proved “A Bridge Too Far”, Brest an original objective of Operation Overlord”, proved “A Port Too Far”. The intense fighting and bombardment over 5 weeks left the city in ruins and the German’s had had plenty of time to extensively sabotage all the port facilities.

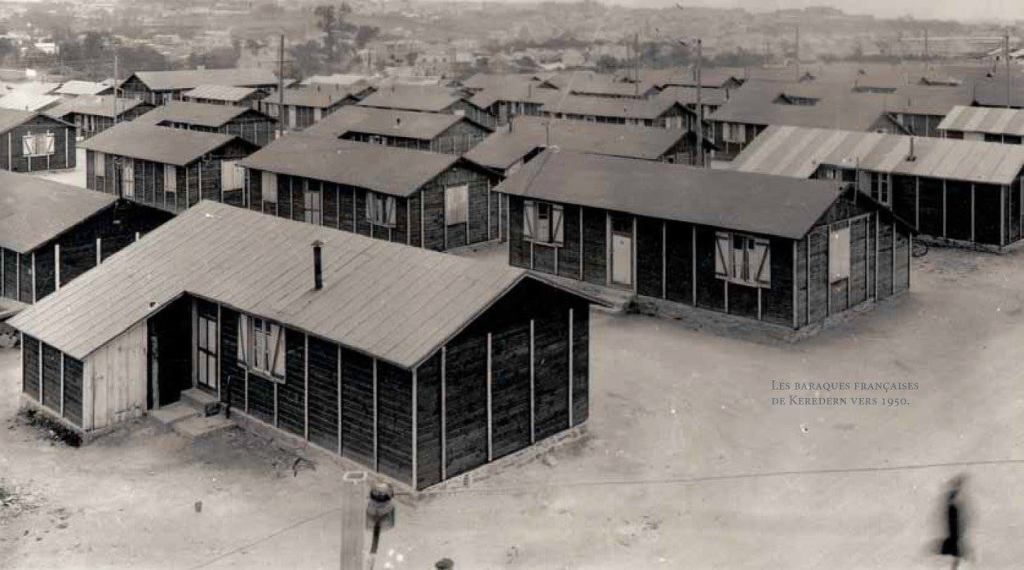

For the Breton people it was bittersweet victory. Although the German commander had ordered the evacuation of the civilian population. The constant ebb and flow of the fighting and the high-profile role of the Resistance had led to two significant massacres of innocent civilians. The city and port facilities would take many years to rebuild. Meanwhile 60,000 people were housed in wooden “Prefab” barrack cities.

On 22 September this year a Remembrance service will be held Fort Montbarey, site of the major British involvement to commemorate all those who served and those who lost their lives in the Battle for Brest.

For a more detailed account of the campaign Stephen J Zalonga’s book “Brittany 1944” is good analysis of the personalities involved, the evolution of the campaign and the constant supply problems that bedevilled the commanders.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to the team at Bovington Tank Museum, Montbarey Museum and the National Army Museum, and to Robert Le Chantoux, Grahame Eckworth, Nick Howes, Ken Lynn, David Page, Gildas Priol, John Smith, Dave Roberts and Mike’s Research